A retenir

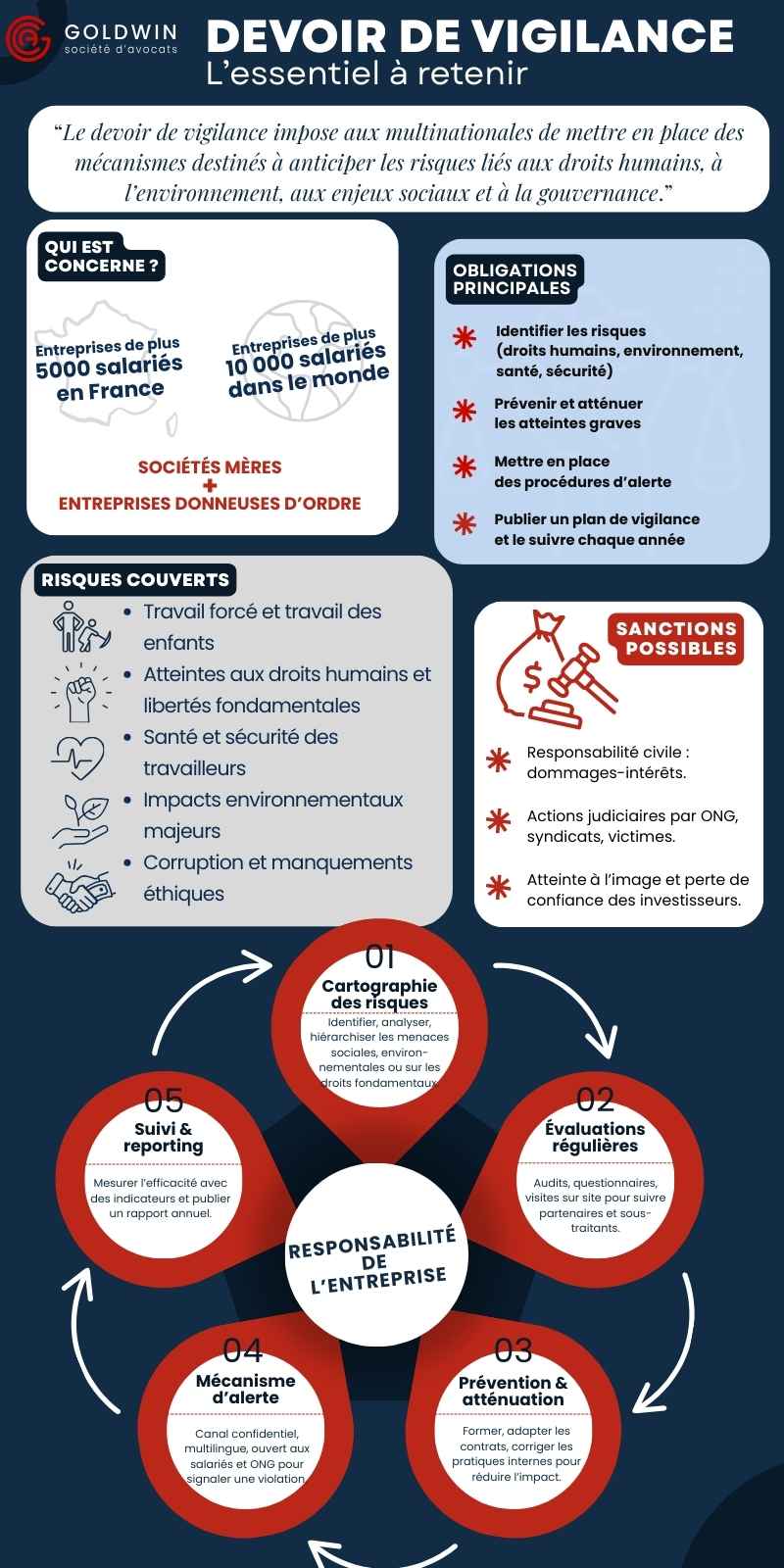

La loi sur le devoir de vigilance, adoptée en 2017, impose aux grandes entreprises d’identifier, prévenir et atténuer les atteintes graves aux droits humains, à la santé, à la sécurité et à l’environnement, dans toute leur chaîne d’approvisionnement.

Les plans de vigilance doivent comporter cinq volets obligatoires : cartographie des risques, évaluation des partenaires, actions préventives, mécanisme d’alerte et suivi régulier des résultats.

En cas de manquement, la responsabilité civile et pénale de l’entreprise ou de sa direction peut être engagée, avec des astreintes financières et une obligation solidaire vis-à-vis des sous-traitants fautifs.

La directive européenne CS3D (2024) renforce le dispositif à l’échelle de l’Union, abaissant les seuils d’application et prévoyant la création d’autorités nationales de contrôle dotées de pouvoirs de sanction.

Le devoir de vigilance devient un levier stratégique : bien appliqué, il protège la réputation, réduit le risque contentieux et peut devenir un avantage concurrentiel dans une économie tournée vers la durabilité.

The duty of vigilance, sometimes also known as the duty of care, is a pioneering French law that requires large companies to draw up and publish a plan to prevent serious violations of human rights, health, safety and the environment. For parent companies and principals, this obligation redefines their compliance strategy. Goldwin Avocats, with its team of business law lawyers in Paris, can help managers to comply with these requirements. Find out in this article how to anticipate the risks and protect your company.

A law born of tragedy and a turning point for CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility)

The law on the duty of vigilance was born out of human and environmental disasters that have marked recent history: Bhopal in India, oil spills in Nigeria, the Chevron affair in Ecuador, the sinking of the Erika and the explosion at the AZF factory in France.

But it was above all the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory in Bangladesh in 2013 that played a decisive role. More than a thousand deaths and thousands of injured revealed to the public the appalling working conditions of the suppliers and subcontractors of Western textile groups. This tragedy showed how difficult it was to hold parent companies and principals responsible.

Since 2013, several bills have been tabled, notably by Dominique Potier. After three and a half years of stormy debate, marked by opposition from a section of the business community, the text was finally adopted in 2017.

Validated by the Constitutional Council, the law now requires large companies to set up a due diligence plan covering their subsidiaries, subcontractors and suppliers, in order to prevent serious human rights and environmental abuses.

What does the 2017 French law say about the duty of vigilance?

Who must apply the duty of care?

Law no. 2017-399 on the duty of care applies to parent companies AND ordering companies:

- Those with at least 5,000 employees in France, or

- 10,000 employees worldwide, including direct and indirect subsidiaries.

The main companies affected are public limited companies (SA) and multi-national groups with high turnover, such as those in the energy, textile, food processing and construction sectors.

When vigilance rhymes with anti-corruption

The Duty of Vigilance Act complements the Sapin 2 Act of 2016, which focused on preventing corruption. Together, they create a broader compliance base: one deals with the risks of corruption, the other with human rights and environmental abuses.

This kind of coordination requires principals to establish global governance to ensure compliance with legal obligations and risk prevention.

The due diligence plan, the backbone of the law

Five compulsory measures to avoid falling foul of the law

Each group bound by these rules must draw up a structured, published and verifiable implementation, which is built around 5 pillars recognised by the Constitutional Council and promulgated on 27 March 2017 (law no. 2017-399):

- Risk mapping: identifying, analysing and prioritising situations likely to cause serious harm, whether social, environmental or linked to fundamental freedoms. This tool must be updated regularly, in light of changes in activities or geopolitical contexts.

- Regular assessment procedures: ongoing assessment of the situation of subcontractors, partners and related entities, through audits, questionnaires or site visits. These assessment procedures make it possible to document the value chain and anticipate environmental or social risks.

- Mitigation and prevention actions: implementation of concrete tools – employee training, specific contractual clauses, review of internal practices – to reduce the potentialnegative impact.

- Alert and collection mechanism: confidential and accessible system, including in several languages, enabling employees or NGOs to report a suspected violation.

- Monitoring and evaluation system: regular checks on the effectiveness of the tools, using quantitative and qualitative indicators, with publication of the financial and non-financial results in an annual report.

How do you set up a compliance plan?

Such a plan cannot be reduced to a simple formal report. It must be seen as a living tool, adjusted to reflect economic realities, established commercial relations and pressure from the European Commission or the European Parliament.

Practical steps include :

- Internal diagnosis: defining priority risk areas and sectors where the impact of the law is greatest (textiles, energy, mining, etc.).

- Analysis of established relationships: examine sensitive partnerships, particularly with subcontractors exposed to violations in third countries.

- Contractual clauses: include specific obligations in contracts to provide a framework for partners and reduce the likelihood of breaches.

- Reporting channels: provide workers, NGOs and any potential victims with a secure, multilingual alert system.

- Monitoring indicators (KPI): measure, at regular intervals, the performance of the plan and the relevance of the measures taken.

This pragmatic approach is reinforced by the future transposition of the work of theEuropean Union, whose Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive has already been the subject of intense debate. Despite attempts at simplification(Omnibus I), it aims to progressively lower the turnover thresholds and broaden the range of ordering companies concerned, with the eventual introduction of national supervisory authorities with powers of investigation and sanction.

Discussions in the French National Assembly’s Economic Affairs Committee have shown that there is a strong awareness that anticipating these rules is preferable to a forced reaction. For some mid-sized structures already subject to the Sapin 2 Act, it is even strategic to capitalise on existing tools to smooth the transition.

Who bears responsibility internally?

The plan must be supported by clear governance: legal department, CSR department, compliance committee.

The Board of Directors remains the ultimate guarantor. In the event of a dispute, it must prove that thecompany has acted with reasonable vigilance if it does not wish to risk being taken to court.

It is at this stage that the role of a firm specialising in business law, such as Goldwin Avocats, is essential in helping you to structure, secure and defend your plans. Prepare your due diligence plans before litigation breaks out.

When non-compliance is costly: litigation and sanctions

Between prevention and reparation

The duty of vigilance combines two complementary approaches:

- Ex ante responsibility: anticipating and avoiding serious harm through risk mapping, assessment procedures and warning mechanisms.

- Ex post responsibility: compensating victims if preventive mechanisms fail, by engaging the company’s civil or criminal liability.

In 2024, La Poste was condemned for failing to comply with its duty of vigilance, marking a turning point: the Paris judicial court ruled that its risk analysis was too incomplete. This decision increases the weight of the litigation and opens the way to other actions against similar groups. On 18 June 2024, the Paris Court of Appeal ruled that the actions against Total Energies and EDF were admissible, while the case against Vigie Groupe (formerly Suez) was declared inadmissible.

In addition to incomplete plans, theduty of vigilance may also entail a joint and several obligation: the principal may be held liable in the same way as the supplier or subcontractor in breach. For example, in the case of undeclared work or employment of undeclared employees, the ordering company may be required to pay the taxes, social security contributions and remuneration owed by its partner at fault.

The civil company at the helm

The implementation of the law relies heavily on the vigilance of civil society. NGOs, trade unions and associations are taking legal action to force recalcitrant groups to meet their obligations.

The action taken against Total Energies, accused of minimising its climate and environmental impact, illustrates the growing pressure being exerted on multinationals. Law no. 2017-399 of 27 March 2017, incorporated into the French Commercial Code (art. L.225-102-4 and L.225-102-5), provides that“in the event of a breach, the judge may order the company to comply with its obligations, where appropriate under penalty payment”. Any person with an interest in the case may serve formal notice on a company and, if it fails to comply within three months, the court may order it to do so and impose fines until it does comply.

In the event of serious non-compliance, particularly in the area of subcontracting, other texts reinforce the penalties:

- Criminal liability(Labour Code, art. L.8224-1 and L.8224-2): up to three years’ imprisonment, a €45,000 fine for an individual and €225,000 for a legal entity, confiscation of equipment and disqualification in the event of concealed work.

- Joint and several civil liability(Labour Code, art. L.8222-2 et seq.): the principal may be required to pay the remuneration owed, reimburse any undue public assistance received and assume responsibility for any social security contributions unpaid by the subcontractor at fault.

This system of sanctions, which is still in its infancy, is evolving in line with court rulings. It confirms that vigilance is more than just a communications exercise: in practice, it engages the legal and financial responsibility of companies.

Europe follows suit

A directive to bring all Member States into line

In 2024, the European Parliament approved the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D). Its aim is to harmonise practices between Member States and extend obligations to more multinationals, including certain SMEs in high-risk sectors. Companies will have to demonstrate that they prevent serious human rights and environmental abuses throughout their value chain.

The new game-changing sectoral rules

The European Union is supplementing this general framework with targeted texts:

- Germany: the Lieferkettengesetz (2023) imposes greater vigilance on the supply chain.

- Netherlands: specific law against child labour.

- Norway (outside the EU, but an inspiration): law on the transparency of supply chains.

- France: pioneer with the 2017 law.

At the same time, European regulations are strengthening due diligence: combating imported deforestation, controlling minerals from conflict zones, banning products manufactured using forced labour.

These measures mark a turning point: Europe is no longer content with general principles, it is imposing binding standards that directly affect companies.

Why the duty of care is a game-changer for businesses

Economic and reputational issues

First and foremost, major French companies must now make due diligence an integral part of their sustainable development strategy. The absence of a credible plan is not without consequences: it can lead to the loss of public contracts, weaken a group’s reputation through a downgrading of its non-financial rating and, in turn, increase the cost of its insurance.

Legal and financial issues

The implications are not limited to reputation. In legal terms, the risks of legal action and fines are very real. A breach that is made public can result in several million euros in penalties and directly engage the civil liability of managers, putting increased pressure on corporate governance.

Societal and climate issues

Lastly, beyond the economic and legal spheres, the duty of care reflects a broader requirement: that of greater social justice and environmental protection. By placing fundamental rights, health and the fight against global warming at the heart of economic activities, the law redefines the role of companies in society as a whole.

Pioneering legislation or an empty shell? The debate is open

A step forward to be consolidated

The Duty of Vigilance Act, adopted after lengthy discussions in the National Assembly, marked a decisive step forward in corporate social responsibility. It aims to make parent companies and contractorsmore accountable to their subsidiaries, subcontractors and suppliers.

However, since its adoption, there has been room for improvement in the practical application of this legislation. Firstly, the lack of case law and the heterogeneity of judicial decisions create legal uncertainty for the companies concerned. Secondly, the means of control remain limited: the State has not provided the courts or the administrative authorities with sufficient resources to assess the quality of the plans published.

Finally, the interpretation of the scope of application still gives rise to differences of opinion, whether on the threshold criteria or on the extent of the social and environmental risks to be covered.

Despite these limitations, the law retains strong symbolic significance. It inspired a European directive in 2024, even though the latter has been weakened by the European Commission ‘s announcements of simplification of standards (Omnibus proposal). The debate therefore remains open: should the obligations be strengthened to guarantee genuine prevention of serious infringements of fundamental rights and the environment, or should the rules be lightened to preserve the competitiveness of multinational companies?

Three clichés to deconstruct

“The law only applies to multinationals”: False.

While the text is primarily aimed at large groups with more than 5,000 employees in France, it indirectly obliges their subsidiaries, subcontractors and suppliers to align themselves with these standards. In practice, every link in the value chain is affected, which means that French groups have to mobilise far beyond their head offices.

“It has no concrete effect”: False.

Several companies have already been taken to court. In 2024, the Paris Court of First Instance ruled against La Poste for inadequate risk mapping. The Total Energies case, which is still pending, also illustrates how NGOs are using the law to denounce climate impacts and greenhouse gas emissions. The initial results show that vigilance is not just a declaratory exercise: it has tangible legal consequences.

“It weakens competitiveness”: Debatable.

Some economic players maintain that this law is a brake on entrepreneurial freedom and that it creates a competitive disadvantage in the face of competitors from outside Europe. Yet others see it as a strategic asset. By incorporating due diligence into their governance, companies can reduce the risk of litigation, improve their image in the eyes of responsible investors and gain easier access to certain types of financing. Ultimately, compliance with regulations can become a competitive advantage in a global economy that is increasingly attentive to sustainability.

Instructions for companies: from theory to action

Who is affected in France today?

Around 270 public limited companies are currently affected. They must have a high turnover and at least 5,000 employees in France, or 10,000 worldwide. The thresholds defined in the text place a direct legal burden on parent companies and, in turn, on their subsidiaries, subcontractors and suppliers.

Tools to demonstrate vigilance

Beyond the plan imposed by the text, an organisation must prove that it is taking concrete and sustainable action. This means documenting its efforts and putting in place verifiable and traceable tools:

- internal and externalaudits carried out by independent third parties

- recognised sustainabilitycertifications or labels ,

- integration of data into ERP or non-financial reporting systems,

- use of monitoring technologies (blockchain, AI, data mining) to analyse the supply chain.

These tools are only of value if they are properly archived and can be used before a judge or supervisory authority. They must also incorporate feedback from stakeholders (NGOs, trade unions, workers’ representatives) in order to strengthen their credibility. Finally, they must cover not only the head office but also our partners abroad, where human rights violations or environmental risks are highest.

In practice, these measures constitute tangible proof of seriousness and greatly reduce the risk of being prosecuted for a plan deemed insufficient.

Why work with a law firm?

Implementing a solid due diligence system is not just a technical issue, but also a legal one. A law firm such as Goldwin Avocats can help with :

- Secure the plan and check that it complies with French legislation and the forthcoming European directive,

- draft and adapt the contractual vigilance clauses with subcontractors and suppliers,

- prepare a defence in the event of a formal notice or litigation before the Paris courts,

- train internal teams to avoid implementation errors.

This support not only reduces the risk of sanctions, but can also transform the legal obligation into a strategic lever.

Conclusion

The duty of care is more than a regulatory constraint: it represents a profound transformation in the way large companies conduct their business in France and Europe. Implementing it requires appropriate measures, rigorous governance and anticipation of human and environmental risks.

Faced with these challenges, the support of an experienced law firm such as Goldwin Avocats can help to secure the process, prevent sanctions and transform this legal obligation into a lever for confidence and competitiveness.

Frequently asked questions about corporate duty of care

How long must a due diligence plan be kept?

The plan must be published every year and adapted as risks change. Earlier versions must be archived to prove the continuity of the approach. In practice, it is recommended that they be kept for at least five years, and even up to ten years for the most sensitive activities.

What is the difference between corporate social responsibility and duty of care?

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is based on a voluntary approach. Companies are free to choose to adopt sustainable or social practices, with no penalties for non-compliance.

On the other hand, the duty of vigilance, introduced by the 2017 law and enshrined in the Commercial Code, requires major groups to draw up and publish a precise plan to identify and prevent serious harm. Failure to comply can result in litigation and penalties.

In both cases, the aim is to place human rights and the environment at the heart of economic activities.

Which authorities monitor compliance with the duty of care?

There is no administrative authority dedicated to monitoring compliance with the duty of care. It is the civil courts that enforce it, relying on actions brought by NGOs, trade unions or associations. Recent case law, in particular that of the Paris judicial court, shows that judges can order ordering companies to correct their plans and meet their obligations.

At European level, the Commission and Parliament are debating a strengthening of the system: creation of national supervisory authorities, powers of investigation, administrative sanctions and dissuasive fines. These changes are designed to close the loopholes that currently exist, where the law can only be enforced through the courts.

Can a vigilance plan cover several countries?

Yes, it must cover all the global activities of a parent company, including subsidiaries, subcontractors and commercial relationships established onan international scale.

Questions fréquentes sur le devoir de vigilance des entreprises